In deze bijdrage wordt ingegaan op een aantal mechanismen die aan de basis staan van onze gezondheid door het eten van groente en fruit. Er is nauwelijks twijfel over dat een voeding met veel groente en fruit gunstig uitpakt op onder andere het gewicht, bloedvetten en glucose, bloeddruk, cardiovasculaire gezondheid en het risico op kanker. Groente en fruit gaan door als ‘gezond’, maar waarom? Meestal is het antwoord: vanwege de micronutriënten en niet te vergeten de vezels. Dat is correct, maar vormt niet het hele verhaal.

In het eerste deel werd, na een inleiding en een discussie over de plant-dierverhouding in onze voeding, de nutriëntendichtheid besproken. In dit tweede en laatste deel komen aan bod: fytochemicaliën, de nitraat-nitriet-stikstofmonoxide-syntheseroute en het zuur-base-evenwicht. De gezondheidsaspecten van vlees/vis, vetzuren en andere eveneens belangrijke onderwerpen worden hier grotendeels buiten beschouwing gelaten.

Fytochemicaliën

Fytochemicaliën, ook wel ‘secondaire metabolieten’ genoemd, worden door planten gemaakt om dieren, insecten en micro-organismen aan te trekken (ten behoeve van de verspreiding hun stuifmeel, zaden en het maken van nutriënten door bv. symbiotische schimmels), voor de bescherming tegen uv-straling, voor de opslag van stikstof, en voor chemische oorlogsvoering met belagers of competerende planten.133,134 Het betreft een breed scala aan stoffen met uiteenlopende structuren, die worden onderverdeeld in secondaire metabolieten die stikstof (zoals alkaloïden, amines, cyanogene glycosiden, glucosinolaten) of geen stikstof bevatten (terpenen, coumarines, saponines, lignanen, flavonoïden).133 Bekende fytochemicaliën zijn resveratrol (druivenpitten), curcumine (geelwortel), sulforafaan (koolsoorten, waaronder broccoli en spruitjes), piperine (zwarte peper), capsaïcine (pepers, gember) en de etherische oliën (vnl. terpenoïden). Cafestol en kahweol zijn di-terpenen in koffiebonen die ons LDL-cholesterol verhogen, maar ze bezitten ook anti-inflammatoire, hepatoprotectieve, anti-kanker, anti-diabetische en anti-osteoclastogenese eigenschappen.97b Vitamine C en de carotenoïden (zoals bètacaroteen) behoren tot de primaire metabolieten (nodig voor groei, ontwikkeling en reproductie) maar zullen waar nodig worden genoemd omdat ze, evenals vele fytochemicaliën, onderdeel zijn van een antioxidantnetwerk.157

Fytochemicaliën hebben tal van gunstige effecten op de gezondheid van mensen en dieren, inclusief de dieren die wij eten.135-140 Ze vervullen functies zoals: substraten voor biochemische reacties, cofactoren van enzymatische reacties, remmers van enzymatische reacties, absorbentia/sequestranten die zich binden aan ongewenste bestanddelen in de darm en ze daarmee elimineren, liganden die celoppervlak- of intracellulaire receptoren agoneren of antagoneren, neutraliseren van reactieve of toxische chemicaliën, verbindingen die de absorptie en/of stabiliteit van essentiële voedingsstoffen verbeteren, selectieve groeifactoren voor nuttige gastro-intestinale bacteriën, fermentatiesubstraten voor nuttige mond-, maag- of darmbacteriën, en selectieve remmers van schadelijke darmbacteriën.140 Sommige, waaronder de fyto-oestrogenen uit soja, vertonen in ons hormonale activiteit.141 Als groep vertonen fytochemicaliën in observationele studies gunstige effecten bij de primaire en secundaire preventie van hart- en vaatziekten.136,136b Een recent overzicht van observationele studies concludeerde dat een hoge consumptie van fytochemicaliën in de meeste onderzoeken geassocieerd is met een lager risico op kanker. Positieve effecten konden echter niet worden bevestigd in de meeste tot nu toe gepubliceerde interventiestudies bij patiënten met kanker en soms is er zelfs sprake van risico op schade. Vanwege de vele verschillende mechanismen is het mogelijk dat het vooral gaat om een cluster van zulke stoffen in planten en niet, of mindere mate, de afzonderlijke componenten.142

Via co-evolutie zijn dieren, zoals wij, ongevoelig(er) geworden voor veel van de fytochemicaliën, die door de plant oorspronkelijk als gifstoffen waren bedoeld tegen hun belagers. Dieren zijn fytochemicaliën zelfs gaan benutten voor eigen doeleinden.133 Ze kunnen ons epigenoom veranderen, waarschijnlijk vooral vanwege hun werking als antioxidant en hun anti-inflammatoire effecten.142a Een (meestal grote) fractie wordt niet opgenomen, moduleert de samenstelling van het darmmicrobioom en zorgt voor de integriteit van de darmwand.140 Dat onze voeding ook bedoeld is voor een gezond microbioom in ons maag-darmkanaal, is geen gedachte die speelde bij onderzoekers die probeerden om de beschikbaarheid van fytochemicaliën te vergroten. Ons lichaam begint niet bij de bekleding van ons maag-darmkanaal en eindigt daar ook niet, en evenmin in het kapseltje van Bowman of de epitheliale bekleding van de exocriene klieren.

De opgenomen fytochemicaliën en ook hun metabolieten die door de microbiota worden gemaakt, kunnen in lage doses stressbestendigheid induceren, waaronder autofagie, DNA-herstel en de expressie van ontgiftende en antioxiderende enzymen.143 Diverse van deze fytochemicaliën werken via uitoefening van een matige oxidatieve stress, die in ons lichaam wordt opgemerkt door het uitermate gevoelige ‘nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2’- systeem (nrf2). Reeds bij geringe oxidatieve stress wordt dit systeem geactiveerd, waarna tal van eiwitten worden geïnduceerd die ons zeer breed beschermen145-159 tegen niet alleen deze secundaire metabolieten, maar ook tegen andere (ook synthetische)159a gifstoffen en zelfs tegen de schadelijke invloed van uv-straling op de huid.159 Eiwitten en enzymen die hierbij tot expressie komen, hebben functies in transport (om gifstoffen de cel uit te werken), rechtstreekse ontgifting (onschadelijk maken door bv. oxidatie, hydroxylering, conjugatie), heem- en ijzermetabolisme, en de koolhydraat- en vetstofwisseling.145-159 Fytochemicaliën moduleren, als zowel agonisten als antagonisten, eveneens de signalering via de arylhydrocarbon-receptor (AhR). Dit is een receptor die sterk verbonden is met ziekte en gezondheid, waaronder maligne groei.159b-f Er is een sterke communicatie tussen het nrf2-systeem en de AhR: zo is resveratrol een nrf2-activator maar een AhR-antagonist.159f,i

Constante lichte, mogelijk alternerende, activering van het nrf2-systeem is noodzakelijk: ‘use it or loose it’ is hierbij van toepassing. Een te lage inname is niet gezond, maar evenzo wordt bij een te hoge dosis het nrf2-systeem over-geactiveerd, waarna, via het NFκB-systeem, een schadelijke inflammatoire reactie wordt gestart.160-167 Constante activering van de arylhydrocarbon-receptor, zoals door het synthetische gif dioxine, is geassocieerd met het ontstaan van kanker en andere ziektes.159b-f Meer is dus ook hier niet beter. De werkzaamheid van secundaire metabolieten lijkt een typische voorbeeld van hormese (gunstig in kleine hoeveelheden) en ook van de uitdrukking ‘wat je niet doodt, maakt je sterker’.168-176

Er zijn geen voedingsnormen voor secundaire plantenmetabolieten. Aangenomen wordt dat hiervan voldoende wordt geconsumeerd via een gevarieerde voeding conform de huidige aanbevelingen voor groente en fruit. Fytochemicaliën maken onder andere deel uit van een antioxidantnetwerk.157 De daarin deelnemende stoffen vormen een delicate balans die niet moet worden verstoord door hoge doseringen van één of meerdere van de netwerkcomponenten.160,167,174,176 Mogelijk is dit de oorzaak van meer (long)kanker in rokers en asbestwerkers door een bètacaroteen-supplement.160 Planten die onder ideale omstandigheden groeien, dus zonder biotische of abiotische stress (‘kasplantjes’), bevatten minder fytochemicaliën, want ook voor planten geldt use it or loose it. De synthese van secundaire metabolieten kost veel energie en dat gaat ten koste van hun groei.133 Stressoren van planten zijn, onder andere, variërende klimatologische omstandigheden, droogte, uv, zware metalen of vraat door insecten of andere dieren.177-185 Planten communiceren rechtstreeks met elkaar via vluchtige organische verbindingen en dat kan ertoe leiden dat ook in de onbeschadigde omringende exemplaren een stressrespons ontstaat, waarna fytochemicaliën preventief worden aangemaakt.186,187

Biotische en abiotische stress is de meest waarschijnlijke reden dat wilde frambozen, aardbeien en bramen twee- tot vijfvoudig hogere hoeveelheden bevatten aan fenolische stoffen dan hun gecultiveerde en gedomesticeerde tegenhangers van dezelfde soort en hetzelfde geslacht.189 Biologisch geteelde tomaten bevatten twee keer hogere fytochemicaliën dan conventioneel gekweekte tegenhangers.53 Arabidopsisplanten die twee dagen in het donker groeien, ondergaan daardoor minder (oxidatieve) stress en bevatten 80% minder vitamine C dan hun tegenhangers die in het licht groeien.190 Interessant is dat vitamine C niet alleen in planten,191,192 maar ook in ons193 is gelinkt aan stress. In de mens is het als cofactor betrokken bij de synthese van catecholaminen en vitamine C wordt, voorafgaand aan cortisol, door onze bijnieren uitgestort bij een stressreactie.194 ‘Stress’, onder andere vanwege de zon, bestaat reeds sinds het ontstaan van het leven, ongeveer 3,2 miljard jaar geleden. Planten en mensen hebben een gemeenschappelijke voorvader die 1,6 miljard jaar teruggaat. Als algen (uiteindelijke planten) en vissen (uiteindelijke mensen) zijn ze onafhankelijk van elkaar pas 500 miljoen jaar geleden het land opgekropen.194a,b Samenvattend is de huidige consensus dat wilde planten, vanwege biotische en abiotische stress, doorgaans hogere gehaltes aan polyfenolen bevatten en ook een hogere antioxidant-activiteit bezitten.195

De hoogste gehaltes aan defensieve fytochemicaliën worden doorgaans aangetroffen in de ontspruitende plant (bv. broccolikiemen), het topmeristeem (waar de plant groeit) en in de organen die belangrijk zijn voor de reproductie (bloemen, vruchten, zaden). Dat zijn de onderdelen die het sterkst dienen te worden beschermd, wat te boek staat als de ‘optimale beschermingstheorie’.133 Witte thee wordt gemaakt uit de jonge delen van de plant, zwarte thee en groene thee uit de oudere delen. Bij zwarte thee worden de blaadjes eerst gefermenteerd. Het totaal fenolgehalte van thee gemaakt van Camellia sinensis (de theeplant) was het hoogst in groene thee, gevolgd door zwarte thee en dan witte thee.196 Het gif wordt in vele gevallen pas geactiveerd bij aanvreten of verwonding, zoals bij de oogst.134 Het onmiddellijk blancheren/invriezen van broccoli na het oogsten of directe verhitting in een microwaveoven denatureert het enzym (myrosinase) dat sulforafaan maakt. Het enzym krijgt dan niet de tijd om deze, als gif bedoelde, stof te maken en daarom bevat geblancheerde/ingevroren broccoli veel minder sulforafaan.197

De nitraat-nitriet-stikstofmonoxide-syntheseroute

Groenten zijn onze belangrijkste bronnen van nitraat (NO3-, ongeveer 80%). Hoge gehaltes worden onder andere aangetroffen in rode bieten, selderij, spinazie en rucola.198 Het nitraatrijk sap van rode bieten is een populair drankje onder sporters geworden (zie beneden)211. Planten kunnen nitraat opslaan in hun vacuolen en doen dat, afhankelijk van de soort, in toenemende mate met de verhoging van het nitraatgehalte van de grond.199 Kunstmest fungeert als een voorname toeleverancier van nitraat. Als een essentieel element beïnvloedt het daarmee de aanwas van eiwit, de celdeling, wortellengte, bloei, groei, en dus het fenotype in brede zin.199,200 Biologische groenten bevatten meestal lagere nitraat- en eiwitgehaltes, maar hebben daarentegen meestal een hogere dichtheid aan fosfaat, totale antioxidantcapaciteit, fenolen, quercetine en vitamine C.201 In een andere studie ging het eveneens om minder stikstof en hoger fosfaat, maar ook om meer titreerbaar zuur (zie ‘zuur-base’).202

Nitraat en nitriet worden als additief gebruikt in onze voeding voor het conserveren en het behoud van de rode kleur van vlees. Ook pekelzout bevat nitriet. Nitraat en nitriet worden onterecht gelinkt aan de negatieve effecten van vlees dat met nitraat en nitriet is geconserveerd.203,204 De totale inname van nitraat als additief bedraagt niet meer dan 5% van de dagelijkse nitraatinname.205 Toxiciteit werd in het verleden vooral toegeschreven aan het aandeel van nitriet (NO2-), omdat het in de maag zou worden omgezet naar de carcinogene nitrosamines.203,204 Dit gebeurt echter niet in de aanwezigheid van voldoende vitamine C of andere antioxidanten, omdat nitriet dan wordt gereduceerd naar stikstofmonoxide (NO).198,223,224 Dr. Bryan, een vooraanstaand NO-onderzoeker, noemt de toevoeging van nitriet voor conservering niet alleen noodzakelijk om ernstige microbiële infecties te voorkomen maar ook gunstig voor onze directe gezondheid door omzetting naar NO.203,204

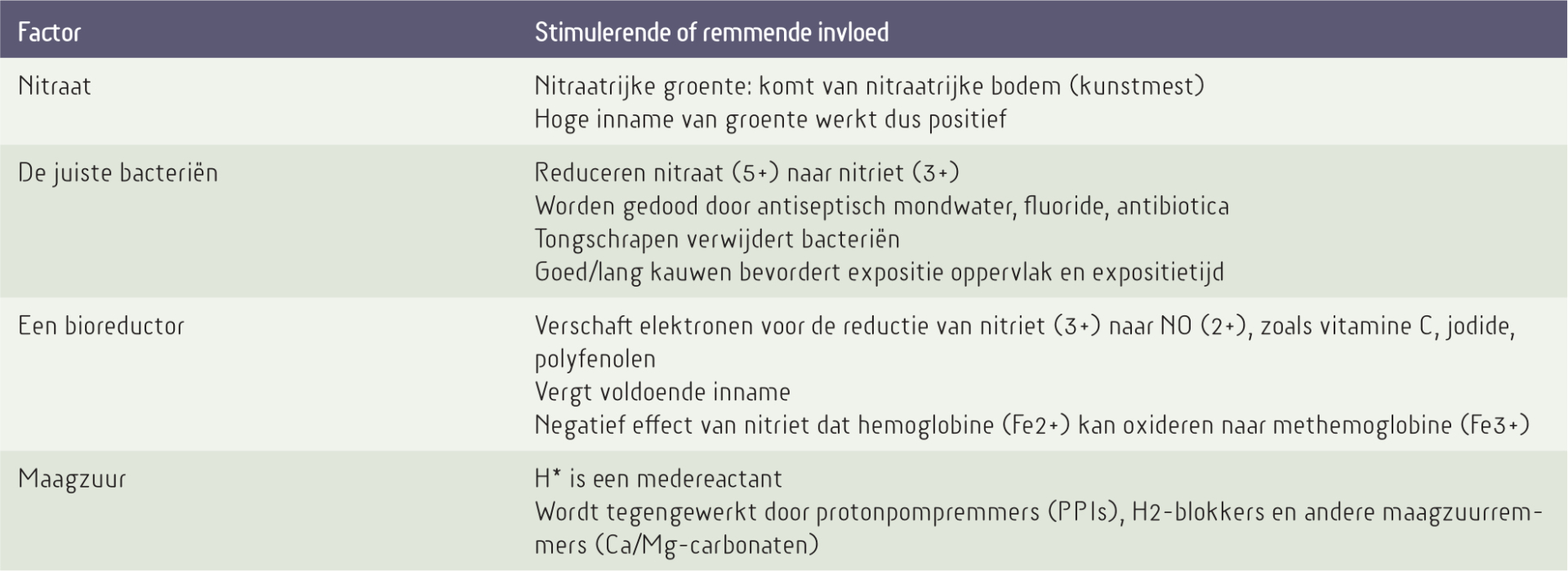

De inname van nitraat door de mens wordt geschat op 31-185 mg/dag (Europa) en 40-100 mg/dag (USA), de nitrietinname op 0-20 mg/dag.198 Een recente Deense studie met 55.754 deelnemers van 50-65 jaar rapporteerde mediane dagelijkse innames van 58 mg nitraat en 1,8 mg nitriet. In die studie kwam het nitraat uit plantaardig materiaal (76%), dierlijk materiaal (10%) en water (5%). De nitrietaandelen uit dierlijk en plantaardig materiaal waren ongeveer gelijk.206 Een deel van het nitraat uit de voeding wordt, samen met een deel van het nitraat dat na opname wordt uitgescheiden door de speekselkliertjes (zie beneden), in de mondholte door de bacteriën enzymatisch gereduceerd naar nitriet (NO2-). Goed en lang kauwen van het voedsel bevordert deze bacteriële omzetting, maar er zijn ook talrijke remmende factoren, zoals het gebruik van aseptisch mondwater, fluoride en antibiotica (tabel 3). In de maag kan het gevormde nitriet verder worden gereduceerd naar NO: een reactief gasvormig radicaal met een zeer korte halfwaardetijd. NO heeft in de maag een antimicrobieel effect, waaronder het doden van Helicobacter pylori. Voor de reductie van nitriet naar NO is maagzuur (H+) nodig als medereactant. Daarom hebben maagzuurremmers, zoals PPIs en H2-blockers, maar ook het gebruik van bicarbonaat, een negatief effect op de vorming van NO. De benodigde elektronen voor de reductie worden geleverd door bioreductoren, zoals vitamine C, jodide of polyfenolen.207-224,228,228a De vitamine C stamt uit de voeding, maar wordt ook uitgescheiden door de speekselkliertjes219 en exocriene kliertjes in de maagwand.226 Gastritis veroorzaakt een lagere uitscheiding van vitamine C door deze maagwandkliertjes, en dat wordt gelinkt aan helicobacter-infectie en hieruit voortkomende maagkanker.226 Jodide komt eveneens uit de voeding en kan na opname ook worden uitgescheiden door de speekselkliertjes en de maagwand.227 Er is dus tenminste recirculatie van nitraat, jodide en vitamine C via speekselkliertjes, en van jodide en vitamine C via maagwandkliertjes. De reactie waarbij nitraat, via nitriet, wordt omgezet naar NO vindt ook plaats in de urineweg en waarschijnlijk in alle exocriene klieren (bv. prostaat, borstklier, pancreas) ten behoeve van lokale antimicrobiële effecten. Voor hun werkzaamheid in de urineweg moeten jodide en vitamine C natuurlijk wel worden uitgescheiden. De huidige ADH voor vitamine C is echter gebaseerd op de grens van de uitscheiding van vitamine C in de urine.225,226,229-231 Iemand heeft bedacht dat ons lichaam ophoudt in het nierbekken…

Nitraat en nitriet kunnen vanuit het maag-darmkanaal worden opgenomen in de circulatie.217 De beschikbaarheid van nitraat is 100%.198 Opgenomen nitriet217 kan zowel enzymatisch als niet-enzymatisch worden omgezet naar NO.218 De halfwaardetijden van nitraat, nitriet en NO in de circulatie bedragen respectievelijk 5-8 uur, 1-5 minuten en 1-2 milliseconden.198 De vorming van NO in ons lichaam gebeurt dus niet alleen via de bekende enzymatische weg uit arginine met behulp van de drie vormen van NO-synthase (NOS).211 In het lichaam fungeert NO als signaalmolecuul met tal van gunstige effecten, waaronder vasodilatatie (bloeddrukverlaging), verlaging van de plaatjesaggregatie, functies in het immuunsysteem en neurotransmissie.218,220 Samengevat is een gezond microbioom in de mondholte als producent van nitriet van groot belang voor de synthese van NO in zowel het maag-darmkanaal als de circulatie (tabel 3).

Opgenomen nitriet kan in de circulatie echter ook door heemijzer (Fe2+) worden gereduceerd naar NO, waarbij hemoglobine oxideert naar methemoglobine (Fe3+). Dat is een toxisch effect omdat methemoglobine geen zuurstof transporteert. Dit proces vormt de huidige grens voor de ‘acceptabele dagelijks innames’ (ADI) van nitraat en nitriet, die door de EFSA worden gesteld op respectievelijk 3,7 en 0,07 mg/kg/dag.205 Dat is voor een persoon van 70 kg ongeveer 260 mg nitraat en 5 mg nitriet. Echter, lang voordat methemoglobine-vorming optreedt heeft een NO-overschot reeds aanleiding gegeven tot een ongewenste bloeddrukdaling.204 Bovendien levert een enkele portie spinazie van 100 g al meer dan 250 mg nitraat.198 De meeste interventiestudies hebben dagdoseringen gebruikt van 400-2.400 mg nitraat232 en tot zo’n 320 mg natriumnitriet.207 Intraveneuze doses van 622 mg natriumnitriet/dag gedurende 14 dagen zijn beschreven.207 De huidige ADI's lijken dus bepaald aan de conservatieve kant.

Ook in de huid (dermis en epidermis) hebben we voorraden NO in de vorm van nitraat, nitriet en S-nitrothiolen (R−S−N=O). Blootstelling aan zonlicht (uvA) bevordert hun omzetting naar NO dat vervolgens ook de circulatie bereikt. Het effect is groter in personen met een witte huid dan met een donkere huid. Vanwege deze NO-bron daalt bij zonnen de bloeddruk en gaat de hartslag omhoog. Bij elitefietsers verhoogt de combinatie van oraal nitraat en blootstelling aan uvA de mitochondriale efficiëntie en prestaties door een lagere zuurstofbehoefte.233 In de winter is vanwege lagere NO-synthese in de huid de bloeddruk 6 mm Hg hoger dan in de winter, hetgeen verantwoordelijk wordt gehouden voor de reeds lang bekende 23% hogere cardiovasculaire mortaliteit in de winter.234 Om dit 6 mm Hg-bloedrukverschil in perspectief te zetten: in een meta-analyse van 167 RCT's bedroeg het bloeddrukverschil tussen een hoge en lage zoutinname door hiervoor gevoelige (hypertensieve) personen met een blanke huidskleur 5,48 mm Hg. In normotensieve mensen is dit verschil slechts 1,27 mm Hg.235 Op de tv wordt uitgebreid verslag gedaan over de gevaren van zout maar de grotere invloeden op onze bloeddruk van de zon en voedingsnitraat worden niet vermeld.

Ten slotte, ademen door de neus verhoogt het circulerend NO eveneens. Deze NO-fractie wordt echter enzymatisch uit arginine gemaakt in de sinussen en wordt bij inademen via de longen opgenomen. Lokaal werkt dit NO antimicrobieel en het verhoogt de zuurstofsaturatie door lokale vasodilatatie van de longvaten.236

Samenvattend, via de reductie van nitraat naar nitriet spelen nitraat-reducerende bacteriën in de mondholte een belangrijke rol in de vorming van NO en daarmee de afweer tegen micro-organismen en het behoud van onze cardiovasculaire gezondheid.211

Zuur-base-evenwicht

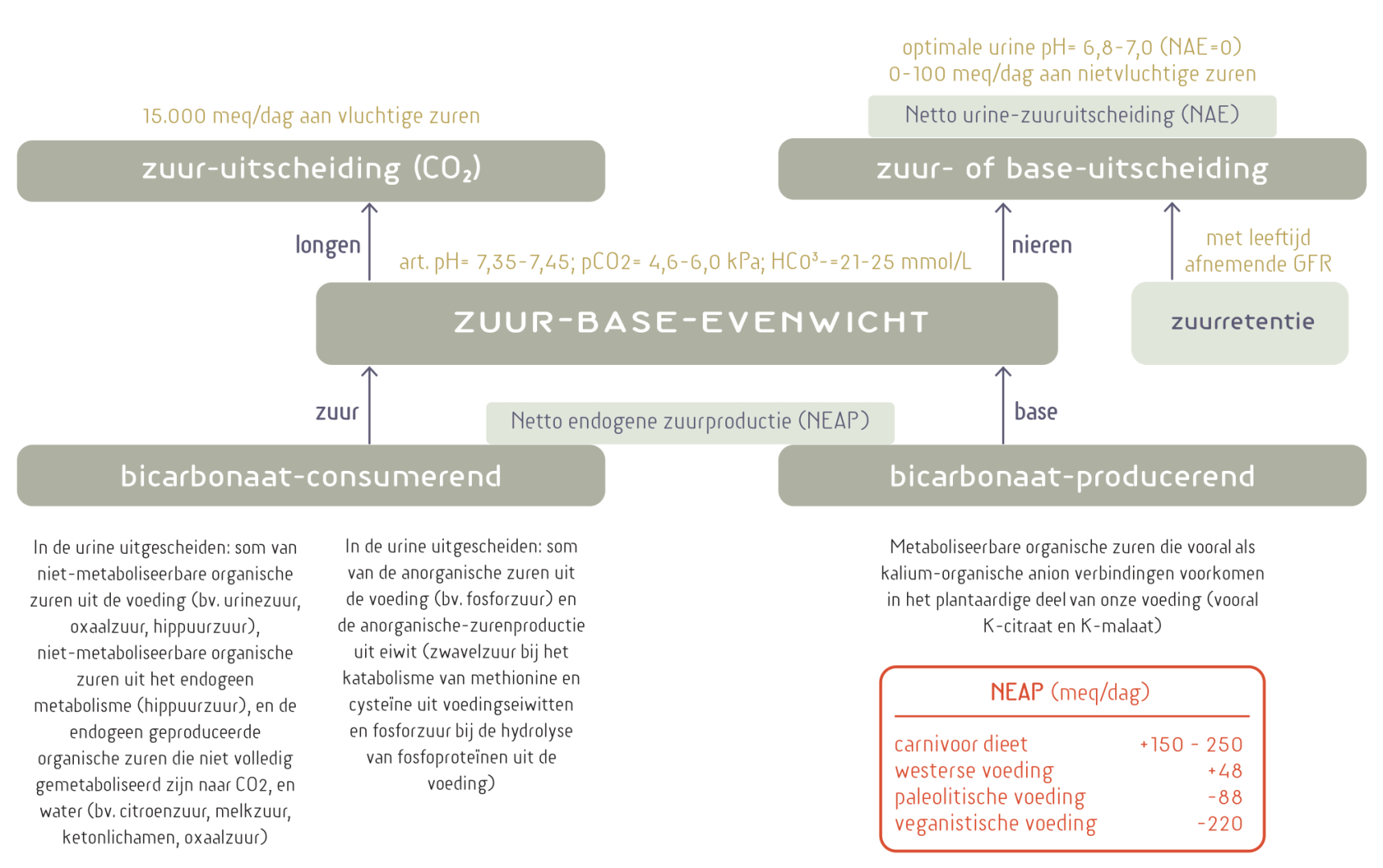

Diverse factoren zijn van belang voor onze zuur-basebalans van het bloed: de 'netto endogene zuurproductie' (NEAP), de long- en nierfunctie, en de leeftijd (figuur 2). De NEAP is het verschil tussen bicarbonaat-consumerende en -producerende factoren. De longen zorgen voor de uitscheiding van de bulk aan (vluchtig) zuur (15.000 meq/dag als CO2) en de nieren voor de uitscheiding van de niet-vluchtige zuren (westerse landen: 70-100 meq/dag, vooral zwavelzuur en fosforzuur). Bij een balans tussen aanvoer en afvoer van zuur hoort een arteriële bloed-pH tussen de 7,35 en 7,45. Deze wordt sterk gereguleerd. CO2-uitscheiding door de longen en van zuur door de nieren zijn dus bepalende factoren bij het constant houden van de arteriële bloed-pH.237-244

Uit figuur 2 is af te lezen dat onze voeding in hoge mate onze zuur-basebalans beïnvloedt via de verhouding tussen vlees/vis en groente/fruit.13,237-251 Hierbij vormt het eten van vlees/vis een zuurbelasting, vooral vanwege het gevormde zwavel- en fosforzuur. Bij het metabolisme van zwavelbevattende aminozuren komt zwavelzuur vrij. Een eiwitrijke voeding bevat eveneens veel fosfaat. De eiwitten in vlees en vis bevatten relatief meer zwavelbevattend methionine dan plantaardige eiwitten, zowel als gewichtspercentage van alle aminozuren, als per kcal eiwit. Dierlijke eiwitten hebben bovendien een iets hogere beschikbaarheid dan plantaardige eiwitten. De consumptie van granen is qua zuur-base-evenwicht nagenoeg neutraal: ze bestaan grotendeels uit koolhydraten, vooral als ze sterk zijn geraffineerd. Koolhydraten worden omgezet naar CO2 en water, en die tellen bij een goede longfunctie niet mee in het zuur-base-evenwicht. Groente en fruit vormen daarentegen een basische belasting vanwege de hierin aanwezige bicarbonaat-vormende nutriënten. Dat zijn de ‘metaboliseerbare organische zuren’, voornamelijk de kaliumzouten van citroenzuur (citraat) en appelzuur (malaat). Planten maken deze in de citroenzuurcyclus en slaan ze samen met kalium op in hun vacuolen. Op deze wijze is de NEAP (figuur 2) afhankelijk van de vlees/vis- versus groente/fruit-verhouding en die kan variëren van zo’n 150-250 meq/dag (carnivoor dieet, zuurvormend) tot -220 meq/dag (veganistische voeding, basevormend).238,245,256

Vóór de landbouwrevolutie was onze geschatte NEAP negatief (i.e. basisch, de NEAP was ongeveer -88 meq/dag), terwijl onze huidige westerse voeding zuurvormend is (NEAP gemiddeld +48 meq/dag).13,18,239,241,245,246 Dat komt vooral door een ongunstige dier/plant-verhouding in onze huidige voeding met te veel vlees/vis ten opzichte van groente/fruit. De reden is niet het eten van meer vlees, maar minder groente/fruit (basisch) dat vanaf de landbouwrevolutie deels werd vervangen door granen (neutraal).241 Gunn et al.252 lieten zien dat een hogere groente/fruit-consumptie (van 4 naar 7,7 porties/dag), ten koste van brood/granen, de NEAP deed dalen met 21,6 meq/dag (van 50,2 naar 28,5), waardoor de urine-pH steeg met 0,68 eenheden (van 5,46 naar 6,14).

De invloed van de veranderde samenstelling door het cultiveren van onze groente en fruit zijn minder goed bekend. In de vrucht beïnvloeden de kaliumzouten van organische zuren (vooral die van citroenzuur en appelzuur) de zuurgraad en spelen daarmee een belangrijke rol in de organoleptische kwaliteit, maar ook de regulatie van de osmotische druk, pH-homeostase en stressbestendigheid van de vrucht.253 De accumulatie van deze kaliumzouten is afhankelijk van genetische variëteit en omgevingsfactoren, waaronder irrigatie, bodemmineralen, uitdunnen en temperatuur.253,254 Ma et al.255 lieten zien dat wilde appels aanzienlijk grotere hoeveelheden appelzuur en citroenzuur bevatten dan gecultiveerde appels, terwijl hun totale suikergehalte en zoetheidsindex ongeveer gelijk zijn. Gelijk suikergehalte en lager citroenzuur is ook vastgesteld voor de gecultiveerde mandarijn256 en de gecultiveerde tomaat.257 Tezamen suggereert dit, dat de mens door selectie van groente en fruit op basis van smaak zijn eigen zuur-base-evenwicht heeft verschoven naar meer ’zuur’ en dat de huidige verstoring van het zuur-base-evenwicht naar een ‘gecompenseerde lichte metabole acidose’ niet alleen ligt aan de consumptie van een hogere dier/plant-ratio. De consequenties hiervan dienen niet te worden onderschat. Op grond van de verschillen in de citraat- en malaatgehaltes in de publicatie van Ma en medewerkers255 laat zich schatten dat het eten van 200 gram gecultiveerde appels (als voorbeeld van de huidige aanbeveling: 200 g fruit per dag) in plaats van 200 g wilde appels, de urine-pH met ongeveer 0,8 eenheden doet dalen. Worden geen appels gegeten, dan gaat de urine-pH omlaag met ongeveer 1,2 eenheden. De uitkomsten tonen de grote invloed die een lagere inname van kaliumcitraat en kaliummalaat uit groente/fruit kan hebben op de ziekten die potentieel uit een chronische lichte zuurbelasting kunnen ontstaan (zie beneden). Vijf gram natriumcitraat onderdrukt 60 meq zuur en 3 gram kaliumcitraat onderdrukt 30 meq zuur.238

Het zuur-base-evenwicht is op zijn beurt belangrijk voor de mineraalhomeostase (en vice versa).248-251 Een hoge netto-zuurbelasting en een lage urine-pH zijn geassocieerd met de uitscheiding van mineralen in de urine, met name calcium en magnesium.248-251,258

De langetermijnconsequenties van een te hoge NEAP is een door de voeding geïnduceerde, en door leeftijd geamplificeerde, toestand van ‘chronische laaggradige metabole acidose’, die relateert aan osteoporose, nierstenen, nierziekte, negatieve stikstofbalans (sarcopenie), lage urine-pH en de ziekten die voortkomen uit insulineresistentie.241,242,259 Een recente meta-analyse van observationele studies concludeerde dat een hoge zuurbelasting vanwege de voeding ook is geassocieerd met zowel het ontstaan van kanker als een slechtere prognose van een reeds bestaande maligniteit.260 Tumorcellen houden van een zure (lactaat) omgeving, terwijl ze er intracellulair een meer basische pH op na houden.261-270 Deze ‘omgekeerde pH-gradiënt’ wordt tegenwoordig beschouwd als één van de ‘kenmerken van kanker’.266 Het bevordert de kankercelproliferatie, vermijding van apoptose, invasieve groei, het metastatisch potentieel, agressiviteit, ontwijking van het immuunsysteem en resistentie tegen behandelingen.267

De allostatische toestand van (respiratoir gecompenseerde) chronische laaggradige metabole acidose leidt tot een iets lagere bloed-pH, die, evenals de lichte daling van de bloed-pH met de leeftijd,271 verdrinkt in de veel ruimere referentiewaarde. Want bij normale long- en nierfuncties kan een zuurbelasting vanwege de voeding met gemak respiratoir worden gecompenseerd, terwijl intacte nieren ruimschoots in staat zijn om het niet-vluchtige deel van het zuur uit te scheiden. Dat doen ze overigens door glutamine af te breken, hetgeen de relatie is met sarcopenie en de uitscheiding van ammonia: er ontstaat een negatieve stikstofbalans. Wel is een hogere zuurbelasting van het lichaam terug te zien in een lage urine-pH. Een gezonde urine-pH is 6,8-7,0. Hierbij is de netto-zuurexcretie door de nieren zo goed als nul.238,239,247,272 Deze optimale urine-pH komt niet overeen met de referentiewaarde van 4,6-8,0 die op websites van gerenommeerde instituten vermeld staat. Jager-verzamelaars in Nieuw Guinea hadden een urine pH van 7,5-9,0.239

De veel aangehaalde ‘Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension’-studie (‘DASH-sodium’ studie) gaat meestal door als een ‘laag-natriumstudie’.273 Het hieruit voortgekomen DASH-dieet benadrukt groente, fruit en vetarme melkproducten, en weinig zout. Het dieet bevat volkorengranen, gevogelte, vis, en noten, en minder rood vlees, snoepgoed en suiker-bevattende dranken dan de controle, typisch Amerikaanse voeding. Overtuigend werd aangetoond dat een lagere natriuminname de bloeddruk deed dalen in personen met een hoog-normale bloeddruk. De bloeddrukdaling (6,7 mm Hg) was echter het meest opvallend als de zoutverlaging (van ‘hoog’ naar ‘laag’) plaatsvond tegen de achtergrond van een typisch Amerikaanse voeding. Tegen de achtergrond van het DASH-dieet, met veel groente en fruit, was de bloeddrukdaling minder uitgesproken (3,0 mm Hg). Door de hogere inname van groente en fruit veroorzaakte het DASH-dieet een bijna tweemaal hogere kaliuminname (2,9 vs. 1,6 g/dag), een daling van de NEAP (van 78 naar 31 meq/dag), en ongetwijfeld ook een hogere (niet gemeten) inname van nitraat en andere nutriënten, zoals fytochemicaliën. De bloeddrukdaling in de DASH-studie lijkt dus vooral op het conto van de combinatie van gunstige eigenschappen van groente en fruit en in mindere mate vanwege een lagere natriuminname. Bovendien moet worden benadrukt dat 41% van de deelnemers in deze studie hoge bloeddruk had bij een gemiddelde BMI van ongeveer 30 kg/m2 en dus gevoegelijk mag worden aangenomen dat ze insulineresistent waren en daarmee dus ook zoutgevoelig.274 Zoals dat bij 30% van de wereldbevolking voorkomt275,276 en daarmee de huidige zoutaanbeveling voor ook werkelijk gezonde mensen heeft bepaald.

Ten slotte kunnen ter illustratie van de gevaren van een chronische laaggradige zuurbelasting genoemd worden de belangrijke studies van Goraya et al.277-289 Haar groep laat reeds sinds ten minste twaalf jaar de niersparende eigenschappen van een meer basische voeding zien. Hun recente (2024) studie werd verricht met 153 hypertensieve patiënten met chronische nierziekte en macroalbuminurie.289 Gedurende vijf jaar kregen deze patiënten de gebruikelijke behandeling, of de gebruikelijke behandeling samen met 2-4 porties (basevormende) groente en fruit, of gebruikelijke behandeling met 2,6-3,3 g/dag natriumbicarbonaat (NaHCO3). De NaHCO3-dosis kwam qua pH-verhogend vermogen overeen met die van de 2-4 porties groente en fruit. Zoals ook in eerdere studies van Goraya aangetoond, bleek de achteruitgang van de nierfunctie langzamer in zowel de groente/fruitgroep als de NaHCO3-groep. De systolische bloeddruk en de cardiovasculaire risicofactoren verbeterden echter sterker in de groente/fruitgroep dan in de groepen die de gebruikelijke behandeling kregen met of zonder NaHCO3.289 De gunstige effecten van groente en fruit zijn in deze patiënten – met hoog risico op progressie van de nierziekte – dus niet alleen toe te schrijven aan de basevormende eigenschappen. Hierbij kan gedacht worden aan de vitaminen/mineralen (o.a. kalium en nitraat) en de fytochemicaliën,290 zoals die in de vorige hoofdstukjes werden besproken.

Conclusies en epiloog

Omdat van de volwassenen in Nederland slechts 29% ten minste 200 g groente (aanbeveling: 250 g) eet per dag, en slechts 18% ten minste 200 g fruit,51 lijken de afnemende vitamine- en mineraalgehaltes in groente en fruit niet de eerste zorg. De meeste winst zit in het opvolgen van de aanbevelingen. Of dat ook geldt voor het afnemende fytochemicaliëngehalte en de invloed op het zuur-base-evenwicht is niet te zeggen, want daarover is nog relatief weinig onderzoek gedaan. Bovendien is ‘leefstijl’ meer dan voeding, want daarbij hebben we ook te maken met chronische stress, onvoldoende beweging, abnormaal microbioom, milieuverontreiniging, slaaptekort, en al hun interacties.

Groente en fruit zijn om vele redenen gezond. De mechanismen zijn met elkaar verweven en ze kunnen als voedingsgroep niet los worden gezien van de andere voedingsgroepen. Extreme voedingen, zoals een veganistische, ketogene of carnivore voeding, verdienen op lange termijn niet de voorkeur, tenzij ze aangevuld worden met de limiterende nutriënten en dat in de hoop dat we deze ook allemaal kennen. Zo wordt tegenwoordig kaliumcitraat toegevoegd aan het ketogeen dieet dat wordt voorgeschreven aan kinderen met refractaire epilepsie.300 Bicarbonaat verdient hierbij niet de voorkeur, want dat neutraliseert de maag-pH, hetgeen ten koste gaat van de productie van NO in de maag.

Voorzichtigheid vanwege de vele onzekere factoren blijft geboden en eigenlijk geldt dat ook voor de ‘zekerheden’ van de Schijf van Vijf. De reden is dat voedingsnormen, zoals de huidige ADH en AI, zich baseren op reductionisme. Ze staan niet vast als een huis en nieuwe inzichten worden dagelijks verkregen. Met ‘reductionisme’ wordt verwezen naar het baseren van deze getallen op slechts een enkel gezondheidsaspect van het betreffende nutriënt. Het meest gevoelige mechanisme kennen we meestal wel (bv. scheurbuik bij vitamine C-gebrek, bloedingen bij vitamine K-tekort), maar de minst gevoelige is de sluipmoordenaar op lange termijn. Dit is de reeds eerder genoemde ‘triage hypothese van Ames’.302-306 Voor sommige stoffen, zoals kaliumcitraat, kaliummalaat en fytochemicaliën bestaat niet eens een ADH/AI.

Een andere reden voor voorzichtigheid is dat de nutriëntgehaltes in de voeding die we tegenwoordig industrieel produceren, afhankelijk zijn van vele variabelen die zich niet laten aflezen van een etiket. Paranoten ‘bevatten veel selenium’ maar afhankelijk van lokale seleniumgehalte in de Braziliaanse bodem varieert het gehalte een factor 34 (2 vs. 68 mg/kg).301 Selectie, veredeling, bodemomstandigheden, ongebalanceerde kunstmest zijn maar een paar van de variabelen, en de opslag en bewerking door de industrie, restaurant en in eigen keuken voegen hier nog extra onzekerheden aan toe.

De consequenties van, per definitie niet waarneembare, subklinische deficiënties spelen zich af op lange termijn.302-306 Ze zijn moeilijk te onderzoeken en derhalve ook niet eenvoudig in kaart te brengen. Ontkennen van hun bestaan door te schermen met ‘gebrek aan bewijs’32 draagt niet bij aan preventie waar menig criticaster ook de mond vol van heeft. Personen die extreme voedingen gebruiken lijken de grootste risico’s te lopen. We zullen moeten erkennen dat we omnivoren zijn en de oplossing voor de vele wereldproblemen niet ligt in het ontkennen van onze fysiologie. Het begrip ‘gezonde voeding’ vergt kennis van onze evolutionaire achtergrond, ecosystemen, voedselketens en onze (patho)fysiologie. Deze holistische zienswijze werd reeds in de jaren zestig verkondigd door die ‘geitenwollen-sokkenfiguren’ en ze hadden groot gelijk!

Evolutionary past

1. Miller, J. B., Mann, N., Cordain, L., Selinger, A., & Green, A. (2018). Paleolithic nutrition: what did our ancestors eat. Genes to Galaxies: The Lecture Series of the 35th Professor Harry Messel International Science School: 12-25 July 2009, 29-42.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Neil-Mann-2/publication/265496576_…

2. Ben-Dor M, Sirtoli R, Barkai R. The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2021 Aug;175 Suppl 72:27-56. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.24247. Epub 2021 Mar 5. PMID: 33675083

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33675083/

Dietary patterns and recommendations

3. Craig WJ, Mangels AR; American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Jul;109(7):1266-82. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.05.027. PMID: 19562864.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19562864/

3a. Landry MJ, Ward CP, Cunanan KM, Durand LR, Perelman D, Robinson JL, Hennings T, Koh L, Dant C, Zeitlin A, Ebel ER, Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL, Gardner CD. Cardiometabolic Effects of Omnivorous vs Vegan Diets in Identical Twins: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Nov 1;6(11):e2344457. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.44457. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Dec 1;6(12):e2350422. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.50422. PMID: 38032644; PMCID: PMC10690456.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38032644/

3b. Capodici A, Mocciaro G, Gori D, Landry MJ, Masini A, Sanmarchi F, Fiore M, Coa AA, Castagna G, Gardner CD, Guaraldi F. Cardiovascular health and cancer risk associated with plant based diets: An umbrella review. PLoS One. 2024 May 15;19(5):e0300711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0300711. PMID: 38748667; PMCID: PMC11095673.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38748667/

3c. Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, Fadnes LT, Keum N, Norat T, Greenwood DC, Riboli E, Vatten LJ, Tonstad S. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2017 Jun 1;46(3):1029-1056. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw319. PMID: 28338764; PMCID: PMC5837313.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28338764/

3d. American Institute for Cancer Research. AICR's Foods that Fight Cancer™ and Foods to Steer Clear Of, Explained. AICR's Foods that Fight Cancer™. No single food can protect you against cancer by itself, accessed 4 November 2014

https://www.aicr.org/cancer-prevention/food-facts/

3e. American Heart Association. ADD COLOR with FRUITS and VEGETABLES, accessed 4 November 2024

https://www.heart.org/-/media/Healthy-Living-Files/Add-Color/Add-Color-…

4. Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016 Dec;116(12):1970-1980. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025. PMID: 27886704.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27886704/

5. 9 verschillende eetstijlen, van vegan tot paleo. Inspiratie 19 juni 2013, accessed 10 october 2024

https://www.culy.nl/inspiratie/9-verschillende-eetstijlen-van-vegan-tot…

6. Kornsteiner M, Singer I, Elmadfa I. Very low n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid status in Austrian vegetarians and vegans. Ann Nutr Metab. 2008;52(1):37-47. doi: 10.1159/000118629. Epub 2008 Feb 28. PMID: 18305382.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18305382/

7. Craig WJ. Health effects of vegan diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 May;89(5):1627S-1633S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736N. Epub 2009 Mar 11. PMID: 19279075.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19279075/

8. Landry MJ, Ward CP, Cunanan KM, Durand LR, Perelman D, Robinson JL, Hennings T, Koh L, Dant C, Zeitlin A, Ebel ER, Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL, Gardner CD. Cardiometabolic Effects of Omnivorous vs Vegan Diets in Identical Twins: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Nov 1;6(11):e2344457. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.44457. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Dec 1;6(12):e2350422. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.50422. PMID: 38032644; PMCID: PMC10690456.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38032644/

9. Sobiecki JG, Appleby PN, Bradbury KE, Key TJ. High compliance with dietary recommendations in a cohort of meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians, and vegans: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Oxford study. Nutr Res. 2016 May;36(5):464-77. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2015.12.016. Epub 2016 Jan 6. PMID: 27101764; PMCID: PMC4844163.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27101764/

10. Varijakshapanicker P, Mckune S, Miller L, Hendrickx S, Balehegn M, Dahl GE, Adesogan AT. Sustainable livestock systems to improve human health, nutrition, and economic status. Anim Front. 2019 Sep 28;9(4):39-50. doi: 10.1093/af/vfz041. PMID: 32002273; PMCID: PMC6951866.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32002273/

11. Mburu M. VEGANISM | Defending Meat – The Nutrition Argument – Parts1-4, accessed 11 08 2024

https://www.insulean.co.uk/veganism-large-brain/

https://www.insulean.co.uk/veganism-short-colon/

https://www.insulean.co.uk/veganism-micronutrients/

https://www.insulean.co.uk/veganism-vegan/

12. Cordain L. Cereal grains: humanity's double-edged sword. World Rev Nutr Diet. 1999;84:19-73. doi: 10.1159/000059677. PMID: 10489816.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10489816/

13. Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, O'Keefe JH, Brand-Miller J. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Feb;81(2):341-54. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341. PMID: 15699220.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15699220/

14. Muskiet, F. A. J. (2005). Evolutionaire geneeskunde U bent wat u eet, maar u moet weer worden wat u at1. Ned Tijdschr Klin Chem Labgeneesk, 30(3), 163-184.

https://scholar.google.nl/scholar?hl=nl&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=muskiet+u+bent+w…

14a. Brüssow H. Nutrition, population growth and disease: a short history of lactose. Environ Microbiol. 2013 Aug;15(8):2154-61. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12117. Epub 2013 Apr 9. PMID: 23574334.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23574334/

15. van Rossum, C. T., Fransen, H. P., Verkaik-Kloosterman, J., Buurma-Rethans, E. J., & Ocké, M. C. (2011). Dutch National Food Consumption Survey 2007-2010: Diet of children and adults aged 7 to 69 years.

https://rivm.openrepository.com/handle/10029/261553

15a. Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, van der Horst H, Jadad AR, Kromhout D, Leonard B, Lorig K, Loureiro MI, van der Meer JW, Schnabel P, Smith R, van Weel C, Smid H. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011 Jul 26;343:d4163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163. PMID: 21791490.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21791490/

16. Van Vliet, S., Provenza, F. D., & Kronberg, S. L. (2021). Health-promoting phytonutrients are higher in grass-fed meat and milk. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 555426.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sustainable-food-systems/articles/…

Ancient diet

17. Cordain L, Miller JB, Eaton SB, Mann N, Holt SH, Speth JD. Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Mar;71(3):682-92. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.3.682. PMID: 10702160.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10702160/

18. Eaton SB, Konner MJ, Cordain L. Diet-dependent acid load, Paleolithic [corrected] nutrition, and evolutionary health promotion. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Feb;91(2):295-7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.29058. Epub 2009 Dec 30. Erratum in: Am J Clin Nutr. 2010 Apr;91(4):1072. PMID: 20042522.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20042522/

19. Konner M, Eaton SB. Paleolithic nutrition: twenty-five years later. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010 Dec;25(6):594-602. doi: 10.1177/0884533610385702. PMID: 21139123.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21139123/

20. Eaton SB, Eaton SB 3rd. Paleolithic vs. modern diets--selected pathophysiological implications. Eur J Nutr. 2000 Apr;39(2):67-70. doi: 10.1007/s003940070032. PMID: 10918987.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10918987/

21. Eaton SB, Cordain L, Lindeberg S. Evolutionary health promotion: a consideration of common counterarguments. Prev Med. 2002 Feb;34(2):119-23. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0966. PMID: 11817904.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11817904/

22. Eaton SB, Eaton SB 3rd, Konner MJ. Paleolithic nutrition revisited: a twelve-year retrospective on its nature and implications. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997 Apr;51(4):207-16. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600389. PMID: 9104571.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9104571/

23. Eaton SB, Konner M. Paleolithic nutrition. A consideration of its nature and current implications. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jan 31;312(5):283-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501313120505. PMID: 2981409.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2981409/

24. Kuipers RS, Luxwolda MF, Dijck-Brouwer DA, Eaton SB, Crawford MA, Cordain L, Muskiet FA. Estimated macronutrient and fatty acid intakes from an East African Paleolithic diet. Br J Nutr. 2010 Dec;104(11):1666-87. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510002679. Epub 2010 Sep 23. PMID: 20860883.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20860883/

25. Sebastian A, Frassetto LA, Sellmeyer DE, Merriam RL, Morris RC Jr. Estimation of the net acid load of the diet of ancestral preagricultural Homo sapiens and their hominid ancestors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Dec;76(6):1308-16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1308. PMID: 12450898.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12450898/

26. Sebastian A, Frassetto LA, Sellmeyer DE, Morris RC Jr. The evolution-informed optimal dietary potassium intake of human beings greatly exceeds current and recommended intakes. Semin Nephrol. 2006 Nov;26(6):447-53. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2006.10.003. PMID: 17275582.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17275582/

27. Sebastian A, Frassetto LA, Sellmeyer DE, Merriam RL, Morris RC Jr. Estimation of the net acid load of the diet of ancestral preagricultural Homo sapiens and their hominid ancestors. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002 Dec;76(6):1308-16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1308. PMID: 12450898.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12450898/

28. Lindeberg S. Paleolithic diets as a model for prevention and treatment of Western disease. Am J Hum Biol. 2012 Mar-Apr;24(2):110-5. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22218. Epub 2012 Jan 19. PMID: 22262579.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22262579/

29. Lindeberg, S., Cordain, L., & Eaton, S. B. (2003). Biological and clinical potential of a palaeolithic diet. Journal of nutritional & environmental medicine, 13(3), 149-160.

https://scholar.google.nl/scholar?hl=nl&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Biological+and+C…

30. O'Keefe JH Jr, Cordain L. Cardiovascular disease resulting from a diet and lifestyle at odds with our Paleolithic genome: how to become a 21st-century hunter-gatherer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004 Jan;79(1):101-8. doi: 10.4065/79.1.101. PMID: 14708953.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14708953/

Evidence Based Medicine

31. HILL AB. THE ENVIRONMENT AND DISEASE: ASSOCIATION OR CAUSATION? Proc R Soc Med. 1965 May;58(5):295-300. PMID: 14283879; PMCID: PMC1898525.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14283879/

32. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996 Jan 13;312(7023):71-2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. PMID: 8555924; PMCID: PMC2349778.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8555924/

Animal/plant ratio

33. Milton K. The critical role played by animal source foods in human (Homo) evolution. J Nutr. 2003 Nov;133(11 Suppl 2):3886S-3892S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3886S. PMID: 14672286.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14672286/

34. Chouraqui JP. Risk Assessment of Micronutrients Deficiency in Vegetarian or Vegan Children: Not So Obvious. Nutrients. 2023 Apr 28;15(9):2129. doi: 10.3390/nu15092129. PMID: 37432244; PMCID: PMC10180846.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37432244/

35. Blomhoff, R., Andersen, R., Arnesen, E. K., Christensen, J. J., Eneroth, H., Erkkola, M., ... & Trolle, E. (2023). Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023: integrating environmental aspects. Nordic Council of Ministers.

https://books.google.nl/books?hl=nl&lr=&id=bl3jEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA2&d…

36. McDougall J. Misinformation on plant proteins. Circulation. 2002 Nov 12;106(20):e148; author reply e148. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042900.87320.d0. PMID: 12427669.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12427669/

37. American Dietetic Association; Dietitians of Canada. Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003 Jun;103(6):748-65. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50142. PMID: 12778049.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12778049/

38. Melina V, Craig W, Levin S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016 Dec;116(12):1970-1980. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025. PMID: 27886704.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27886704/

39. Mariotti F, Gardner CD. Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets-A Review. Nutrients. 2019 Nov 4;11(11):2661. doi: 10.3390/nu11112661. PMID: 31690027; PMCID: PMC6893534.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31690027/

40. Wang T, Masedunskas A, Willett WC, Fontana L. Vegetarian and vegan diets: benefits and drawbacks. Eur Heart J. 2023 Sep 21;44(36):3423-3439. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad436. PMID: 37450568; PMCID: PMC10516628.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37450568/

41. Mullie P, Deliens T, Clarys P. Vitamin C in East-Greenland traditional nutrition: a reanalysis of the Høygaard nutritional data (1936-1937). Int J Circumpolar Health. 2021 Dec;80(1):1951471. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2021.1951471. PMID: 34232845; PMCID: PMC8266228.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34232845/

42. Mullie P, Deliens T, Clarys P. East-Greenland traditional nutrition: a reanalysis of the Inuit energy balance and the macronutrient consumption from the Høygaard nutritional data (1936-1937). Int J Circumpolar Health. 2021 Dec;80(1):1932184. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2021.1932184. PMID: 34058960; PMCID: PMC8172218.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34058960/

43. Nori Sheets on the Carnivore Diet? Yes or No? Find out… Written by Craig, 31 March 2024, accessed 16 October 2024

https://diaryofacarnivore.com/carnivore-foods/nori-sheets-on-the-carniv…

Nutrient density

44. World Health Organization (WHO). Preventing and controlling micronutrient deficiencies in populations affected by an emergency Multiple vitamin and mineral supplements for pregnant and lactating women, and for children aged 6 to 59 months. Accessed 16 October 2024

https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/WHO-WFP-UNICEF-statement-micron…

45. World Health Organization (WHO). Micronutrients, accessed 16 Ocober 2024.

https://www.who.int/health-topics/micronutrients#tab=tab_1

46. Passarelli S, Free CM, Shepon A, Beal T, Batis C, Golden CD. Global estimation of dietary micronutrient inadequacies: a modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2024 Oct;12(10):e1590-e1599. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(24)00276-6. Epub 2024 Aug 29. PMID: 39218000; PMCID: PMC11426101.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39218000/

47. Global Dietary Database, the World Bank, and dietary recall surveys in 31 countries, accessed 16 October 2024

https://emlab-ucsb.shinyapps.io/global_intake_inaqequacies/

47a. Bailey RL, West KP Jr, Black RE. The epidemiology of global micronutrient deficiencies. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66 Suppl 2:22-33. doi: 10.1159/000371618. Epub 2015 Jun 2. PMID: 26045325.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26045325/

47b. Drewnowski A. Defining nutrient density: development and validation of the nutrient rich foods index. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009 Aug;28(4):421S-426S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10718106. PMID: 20368382.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20368382/

48. Triggiani V, Tafaro E, Giagulli VA, Sabbà C, Resta F, Licchelli B, Guastamacchia E. Role of iodine, selenium and other micronutrients in thyroid function and disorders. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2009 Sep;9(3):277-94. doi: 10.2174/187153009789044392. Epub 2009 Sep 1. PMID: 19594417.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19594417/

49. Prasad AS. Impact of the discovery of human zinc deficiency on health. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2014 Oct;28(4):357-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.09.002. Epub 2014 Sep 16. PMID: 25260885.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25260885/

50. Shreenath, A. P., Hashmi, M. F., & Dooley, J. (2023). Selenium deficiency. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482260/

51. RIVM, voedselconsumptie peiling. Verandering consumptie groente en fruit. Accesse 16 October 2024.

https://www.wateetnederland.nl/resultaten/veranderingen/verandering-con…

52. Davis DR, Epp MD, Riordan HD. Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden crops, 1950 to 1999. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004 Dec;23(6):669-82. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719409. PMID: 15637215.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15637215/

52a. Workinger JL, Doyle RP, Bortz J. Challenges in the Diagnosis of Magnesium Status. Nutrients. 2018 Sep 1;10(9):1202. doi: 10.3390/nu10091202. PMID: 30200431; PMCID: PMC6163803.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30200431/

53. Mitchell AE, Hong YJ, Koh E, Barrett DM, Bryant DE, Denison RF, Kaffka S. Ten-year comparison of the influence of organic and conventional crop management practices on the content of flavonoids in tomatoes. J Agric Food Chem. 2007 Jul 25;55(15):6154-9. doi: 10.1021/jf070344+. Epub 2007 Jun 23. PMID: 17590007.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17590007/

54. Drewnowski A, Fulgoni VL 3rd. Nutrient density: principles and evaluation tools. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 May;99(5 Suppl):1223S-8S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.073395. Epub 2014 Mar 19. PMID: 24646818.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24646818/

54a. Chouraqui JP. Risk Assessment of Micronutrients Deficiency in Vegetarian or Vegan Children: Not So Obvious. Nutrients. 2023 Apr 28;15(9):2129. doi: 10.3390/nu15092129. PMID: 37432244; PMCID: PMC10180846.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37432244/

55. Varijakshapanicker P, Mckune S, Miller L, Hendrickx S, Balehegn M, Dahl GE, Adesogan AT. Sustainable livestock systems to improve human health, nutrition, and economic status. Anim Front. 2019 Sep 28;9(4):39-50. doi: 10.1093/af/vfz041. PMID: 32002273; PMCID: PMC6951866.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32002273/

56. Gupta S. Brain food: Clever eating. Nature. 2016 Mar 3;531(7592):S12-3. doi: 10.1038/531S12a. PMID: 26934519.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26934519/

57. Fordyce, F. M. (2013). Selenium Deficiency and Toxicity in the Environment, Selinus, Olle, Essentials of Medical Geology: Revised Edition pp. 375-416.

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-007-4375-5_16

58. Lyons G. Biofortification of Cereals With Foliar Selenium and Iodine Could Reduce Hypothyroidism. Front Plant Sci. 2018 Jun 8;9:730. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00730. PMID: 29951072; PMCID: PMC6008543.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29951072/

59. Recommendations, N. N. (2014). Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012: Integrating nutrition and physical activity. Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 627.

https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:704251/fulltext01.pdf

60. Farmer B, Larson BT, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Rainville AJ, Liepa GU. A vegetarian dietary pattern as a nutrient-dense approach to weight management: an analysis of the national health and nutrition examination survey 1999-2004. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011 Jun;111(6):819-27. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.012. PMID: 21616194.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21616194/

61. Neufingerl N, Eilander A. Nutrient Intake and Status in Adults Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2021 Dec 23;14(1):29. doi: 10.3390/nu14010029. PMID: 35010904; PMCID: PMC8746448.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35010904/

62. Bhardwaj RL, Parashar A, Parewa HP, Vyas L. An Alarming Decline in the Nutritional Quality of Foods: The Biggest Challenge for Future Generations' Health. Foods. 2024 Mar 14;13(6):877. doi: 10.3390/foods13060877. PMID: 38540869; PMCID: PMC10969708.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38540869/

62a. Bevat onze voeding minder voedingsstoffen dan vroeger? Informatiecentrum voedingssupplementen en gezondheid (IVG), accessed 1 november 2024

https://www.ivg-info.nl/voedingssupplementen/mineralen/bevat-onze-voedi…

62b. Rietra, R. P. J. J. Achteruitgang van nutriëntengehalten in voedselgewassen door een verminderde bodemkwaliteit?. No. 1439. Alterra, 2007.

https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/358598

63. Davis, D. R. (2009). Declining fruit and vegetable nutrient composition: what is the evidence?. HortScience, 44(1), 15-19.

https://journals.ashs.org/hortsci/view/journals/hortsci/44/1/article-p1…

64. Fan MS, Zhao FJ, Poulton PR, McGrath SP. Historical changes in the concentrations of selenium in soil and wheat grain from the Broadbalk experiment over the last 160 years. Sci Total Environ. 2008 Jan 25;389(2-3):532-8. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.08.024. Epub 2007 Sep 20. PMID: 17888491.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17888491/

65. Fan MS, Zhao FJ, Fairweather-Tait SJ, Poulton PR, Dunham SJ, McGrath SP. Evidence of decreasing mineral density in wheat grain over the last 160 years. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2008;22(4):315-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2008.07.002. Epub 2008 Sep 17. PMID: 19013359.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19013359/

66. Myers SS, Wessells KR, Kloog I, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Effect of increased concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide on the global threat of zinc deficiency: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015 Oct;3(10):e639-45. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00093-5. Epub 2015 Jul 15. PMID: 26189102; PMCID: PMC4784541.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26189102/

67. Dong J, Gruda N, Lam SK, Li X, Duan Z. Effects of Elevated CO2 on Nutritional Quality of Vegetables: A Review. Front Plant Sci. 2018 Aug 15;9:924. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00924. PMID: 30158939; PMCID: PMC6104417.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30158939/

68. Smith, M. R., & Myers, S. S. (2018). Impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on global human nutrition. Nature Climate Change, 8(9), 834-839.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-018-0253-3

69. Waarom er tegenwoordig minder mineralen in ons eten zitten, maar zorgen niet nodig zijn. niet nodig zijn. 24-09-2024 18:12 Klimaat en energie Auteur: Nina Hartenberg, accessed 16 October 2024

https://eenvandaag.avrotros.nl/item/waarom-er-tegenwoordig-minder-miner…

70. Muskiet FAJ, Schaafsma G, Dijck-Brouwer DAJ. Nederland is nu ook officieel seleniumdeficiënt. Voedingsgeneeskunde 6-2023, 70-71.

https://www.voedingsgeneeskunde.nl/vg-24-6/nederland-nu-ook-officieel-s…

71. Terry N, Zayed AM, De Souza MP, Tarun AS. SELENIUM IN HIGHER PLANTS. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000 Jun;51:401-432. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.401. PMID: 15012198.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15012198/

72. Nielsen, F. H. (2000). Evolutionary events culminating in specific minerals becoming essential for life. European journal of nutrition, 39, 62-66.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s003940050003

73. Varo, P., Alfthan, G., Ekholm, P., Aro, A., & Koivistoinen, P. (1988). Selenium intake and serum selenium in Finland: effects of soil fertilization with selenium. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 48(2), 324-329.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002916523163799

74. Alfthan, G., Eurola, M., Ekholm, P., Venäläinen, E. R., Root, T., Korkalainen, K., ... & Aro, A. (2015). Selenium Working Group Effects of nationwide addition of selenium to fertilizers on foods, and animal and human health in Finland: From deficiency to optimal selenium status of the population. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol, 31, 142-147.

https://researchportal.helsinki.fi/en/publications/effects-of-nationwid…

75. Ros, G. H., Van Rotterdam, A. M. D., Bussink, D. W., & Bindraban, P. S. (2016). Selenium fertilization strategies for bio-fortification of food: an agro-ecosystem approach. Plant and Soil, 404, 99-112.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11104-016-2830-4

76. Lyons, G. (2018). Biofortification of cereals with foliar selenium and iodine could reduce hypothyroidism. Frontiers in Plant Science, 9, 730.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/plant-science/articles/10.3389/fpl…

77. Duborská, E., Šebesta, M., Matulová, M., Zvěřina, O., & Urík, M. (2022). Current Strategies for Selenium and Iodine Biofortification in Crop Plants. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4717.

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/14/22/4717

78. van Volksgezondheid, M., & en Sport, W. (2008). Naar behoud van een optimale jodiuminname-Advies-Gezondheidsraad. Accessed 17 October 2024

https://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/documenten/adviezen/2008/09/30/naar-beho…

79. Ren Q, Fan J, Zhang Z, Zheng X, Delong GR. An environmental approach to correcting iodine deficiency: supplementing iodine in soil by iodination of irrigation water in remote areas. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2008;22(1):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2007.09.003. Epub 2007 Oct 17. PMID: 18319134.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18319134/

79a. Pereira, Leonel, and João Cotas. "Historical use of seaweed as an agricultural fertilizer in the European Atlantic area." Seaweeds as plant fertilizer, agricultural biostimulants and animal fodder. CRC Press, 2019. 1-22.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9780429487156-1/his…

80. Weng, H., Hong, C., Xia, T., Bao, L., Liu, H., & Li, D. (2013). Iodine biofortification of vegetable plants—An innovative method for iodine supplementation. Chinese Science Bulletin, 58, 2066-2072.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11434-013-5709-2

81. Duborská E, Šebesta M, Matulová M, Zvěřina O, Urík M. Current Strategies for Selenium and Iodine Biofortification in Crop Plants. Nutrients. 2022 Nov 8;14(22):4717. doi: 10.3390/nu14224717. PMID: 36432402; PMCID: PMC9694821.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36432402/

82. Hong, C. L., Weng, H. X., Qin, Y. C., Yan, A. L., & Xie, L. L. (2008). Transfer of iodine from soil to vegetables by applying exogenous iodine. Agronomy for sustainable development, 28, 575-583.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1051/agro:2008033

83. Raghunandan, B. L., Vyas, R. V., Patel, H. K., & Jhala, Y. K. (2019). Perspectives of seaweed as organic fertilizer in agriculture. Soil fertility management for sustainable development, 267-289.

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-13-5904-0_13

84. Jalali P, Roosta HR, Khodadadi M, Torkashvand AM, Jahromi MG. Effects of brown seaweed extract, silicon, and selenium on fruit quality and yield of tomato under different substrates. PLoS One. 2022 Dec 8;17(12):e0277923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277923. PMID: 36480512; PMCID: PMC9731418.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36480512/

85. Karthik, T., & Jayasri, M. A. (2023). Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 14, 100748.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Karthik_Thangaraj5/publication/373…

86. Cristea, G., Dehelean, A., Puscas, R., Covaciu, F. D., Hategan, A. R., Müller Molnár, C., & Magdas, D. A. (2023). Characterization and Differentiation of Wild and Cultivated Berries Based on Isotopic and Elemental Profiles. Applied Sciences, 13(5), 2980.

https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/13/5/2980

86a. Castañeda-Loaiza V, Oliveira M, Santos T, Schüler L, Lima AR, Gama F, Salazar M, Neng NR, Nogueira JMF, Varela J, Barreira L. Wild vs cultivated halophytes: Nutritional and functional differences. Food Chem. 2020 Dec 15;333:127536. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127536. Epub 2020 Jul 9. PMID: 32707417.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32707417/

86b. Srivastava, Reema. "Nutritional Quality of Some Cultivated and Wild Species of Amaranthus L." International Journal of pharmaceutical sciences and research 2.12 (2011): 3152.

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=c0aeda92…

86c. Lei, Zhangying, et al. "From wild to cultivated crops: general shift in morphological and physiological traits for yield enhancement following domestication." Crop and Environment (2024).

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2773126X24000108

86d. Zhang, Hengyou, et al. "Back into the wild—Apply untapped genetic diversity of wild relatives for crop improvement." Evolutionary applications 10.1 (2017): 5-24.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/eva.12434

86e. Hebelstrup KH. Differences in nutritional quality between wild and domesticated forms of barley and emmer wheat. Plant Sci. 2017 Mar;256:1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.12.006. Epub 2016 Dec 15. PMID: 28167022.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28167022/

86f. Fernandez AR, Sáez A, Quintero C, Gleiser G, Aizen MA. Intentional and unintentional selection during plant domestication: herbivore damage, plant defensive traits and nutritional quality of fruit and seed crops. New Phytol. 2021 Aug;231(4):1586-1598. doi: 10.1111/nph.17452. Epub 2021 Jun 17. PMID: 33977519.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33977519/

87. Earthwise Organics. Mineral wheel, accessed 20 October 2024

https://earthwiseagriculture.net/the-mineral-wheel/

88. Xie, K., Cakmak, I., Wang, S., Zhang, F., & Guo, S. (2021). Synergistic and antagonistic interactions between potassium and magnesium in higher plants. The Crop Journal, 9(2), 249-256.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214514120301732

89. Cazzola R, Della Porta M, Manoni M, Iotti S, Pinotti L, Maier JA. Going to the roots of reduced magnesium dietary intake: A tradeoff between climate changes and sources. Heliyon. 2020 Nov 3;6(11):e05390. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05390. PMID: 33204877; PMCID: PMC7649274.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33204877/

90. García-Herrera P, Morales P, Cámara M, Fernández-Ruiz V, Tardío J, Sánchez-Mata MC. Nutritional and Phytochemical Composition of Mediterranean Wild Vegetables after Culinary Treatment. Foods. 2020 Nov 28;9(12):1761. doi: 10.3390/foods9121761. PMID: 33260734; PMCID: PMC7760095.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33260734/

91. Nogoy KMC, Sun B, Shin S, Lee Y, Zi Li X, Choi SH, Park S. Fatty Acid Composition of Grain- and Grass-Fed Beef and Their Nutritional Value and Health Implication. Food Sci Anim Resour. 2022 Jan;42(1):18-33. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2021.e73. Epub 2022 Jan 1. PMID: 35028571; PMCID: PMC8728510.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35028571/

92. Davis H, Magistrali A, Butler G, Stergiadis S. Nutritional Benefits from Fatty Acids in Organic and Grass-Fed Beef. Foods. 2022 Feb 23;11(5):646. doi: 10.3390/foods11050646. PMID: 35267281; PMCID: PMC8909876.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35267281/

93. Daley CA, Abbott A, Doyle PS, Nader GA, Larson S. A review of fatty acid profiles and antioxidant content in grass-fed and grain-fed beef. Nutr J. 2010 Mar 10;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-10. PMID: 20219103; PMCID: PMC2846864.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20219103/

94. van Vliet S, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Provenza FD, Kronberg SL, Pieper CF, Huffman KM. A metabolomics comparison of plant-based meat and grass-fed meat indicates large nutritional differences despite comparable Nutrition Facts panels. Sci Rep. 2021 Jul 5;11(1):13828. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93100-3. PMID: 34226581; PMCID: PMC8257669.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34226581/

95. Dillard, C. J., & German, J. B. (2000). Phytochemicals: nutraceuticals and human health. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 80(12), 1744-1756.

https://scijournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/1097-0010(2…

96. Li C, Bishop TRP, Imamura F, Sharp SJ, Pearce M, Brage S, Ong KK, Ahsan H, Bes-Rastrollo M, Beulens JWJ, den Braver N, Byberg L, Canhada S, Chen Z, Chung HF, Cortés-Valencia A, Djousse L, Drouin-Chartier JP, Du H, Du S, Duncan BB, Gaziano JM, Gordon-Larsen P, Goto A, Haghighatdoost F, Härkänen T, Hashemian M, Hu FB, Ittermann T, Järvinen R, Kakkoura MG, Neelakantan N, Knekt P, Lajous M, Li Y, Magliano DJ, Malekzadeh R, Le Marchand L, Marques-Vidal P, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Maskarinec G, Mishra GD, Mohammadifard N, O'Donoghue G, O'Gorman D, Popkin B, Poustchi H, Sarrafzadegan N, Sawada N, Schmidt MI, Shaw JE, Soedamah-Muthu S, Stern D, Tong L, van Dam RM, Völzke H, Willett WC, Wolk A, Yu C; EPIC-InterAct Consortium; Forouhi NG, Wareham NJ. Meat consumption and incident type 2 diabetes: an individual-participant federated meta-analysis of 1·97 million adults with 100 000 incident cases from 31 cohorts in 20 countries. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024 Sep;12(9):619-630. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00179-7. PMID: 39174161.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39174161/

97. O'Keefe JH Jr, Cordain L. Cardiovascular disease resulting from a diet and lifestyle at odds with our Paleolithic genome: how to become a 21st-century hunter-gatherer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004 Jan;79(1):101-8. doi: 10.4065/79.1.101. PMID: 14708953.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14708953/

97a. Siddiqui, Tohfa, et al. "Terpenoids in Essential Oils: chemistry, classification, and potential impact on human health and industry." Phytomedicine plus (2024): 100549.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667031324000277

97b. Ren Y, Wang C, Xu J, Wang S. Cafestol and Kahweol: A Review on Their Bioactivities and Pharmacological Properties. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Aug 30;20(17):4238. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174238. PMID: 31480213; PMCID: PMC6747192.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6747192/

98. Soriano, A., & Sánchez-García, C. (2021). Nutritional composition of game meat from wild species harvested in Europe. Meat and Nutrition, 77-100.

https://books.google.nl/books?hl=nl&lr=&id=CQc_EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA77&…

99. Frankel 2nd, E. N. (2005). Lipid oxidation 2nd eidtion. Dundee, Scotland: The Oily Press LTD.

https://shop.elsevier.com/books/lipid-oxidation/frankel/978-0-9531949-8…

100. Morales A, Marmesat S, Dobarganes MC, Márquez-Ruiz G, Velasco J. Quantitative analysis of hydroperoxy-, keto- and hydroxy-dienes in refined vegetable oils. J Chromatogr A. 2012 Mar 16;1229:190-7. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.01.039. Epub 2012 Jan 24. PMID: 22321954.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22321954/

101. Bulanda S, Janoszka B. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Roasted Pork Meat and the Effect of Dried Fruits on PAH Content. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 10;20(6):4922. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20064922. PMID: 36981831; PMCID: PMC10049194.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10049194/#:~:text=PAHs%20in%20….

102. Sivasubramanian BP, Dave M, Panchal V, Saifa-Bonsu J, Konka S, Noei F, Nagaraj S, Terpari U, Savani P, Vekaria PH, Samala Venkata V, Manjani L. Comprehensive Review of Red Meat Consumption and the Risk of Cancer. Cureus. 2023 Sep 15;15(9):e45324. doi: 10.7759/cureus.45324. PMID: 37849565; PMCID: PMC10577092.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37849565/

103. Qigang N, Afra A, Ramírez-Coronel AA, Turki Jalil A, Mohammadi MJ, Gatea MA, Efriza, Asban P, Mousavi SK, Kanani P, Mombeni Kazemi F, Hormati M, Kiani F. The effect of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biomarkers on cardiovascular diseases. Rev Environ Health. 2023 Oct 2. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2023-0070. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37775307.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37775307/

104. Domínguez R, Pateiro M, Gagaoua M, Barba FJ, Zhang W, Lorenzo JM. A Comprehensive Review on Lipid Oxidation in Meat and Meat Products. Antioxidants (Basel). 2019 Sep 25;8(10):429. doi: 10.3390/antiox8100429. PMID: 31557858; PMCID: PMC6827023.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31557858/

105. Beddows CG, Jagait C, Kelly MJ. Preservation of alpha-tocopherol in sunflower oil by herbs and spices. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2000 Sep;51(5):327-39. doi: 10.1080/096374800426920. PMID: 11103298.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11103298/

106. Sargent JR. Fish oils and human diet. Br J Nutr. 1997 Jul;78 Suppl 1:S5-13. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970131. PMID: 9292771.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9292771/

107. Sargent JR, Tacon AG. Development of farmed fish: a nutritionally necessary alternative to meat. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999 May;58(2):377-83. doi: 10.1017/s0029665199001366. PMID: 10466180.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10466180/

108. Farmed Salmon vs. Wild Salmon. Washinton State Department of Health, accessed 2 May 2024

https://doh.wa.gov/community-and-environment/food/fish/farmed-salmon#:~….

109. Willer, D. F., Newton, R., Malcorps, W., Kok, B., Little, D., Lofstedt, A., ... & Robinson, J. P. (2024). Wild fish consumption can balance nutrient retention in farmed fish. Nature Food, 1-9.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-024-00932-z

110. Neufingerl N, Eilander A. Nutrient Intake and Status in Children and Adolescents Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023 Oct 11;15(20):4341. doi: 10.3390/nu15204341. PMID: 37892416; PMCID: PMC10609337.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37892416/

111. Mann GV, Shaffer RD, Rich A. Physical fitness and immunity to heart-disease in Masai. Lancet. 1965 Dec 25;2(7426):1308-10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(65)92337-8. PMID: 4165302.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4165302/

112. Taylor CB, Ho KJ. Studies on the Masai. Am J Clin Nutr. 1971 Nov;24(11):1291-3. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/24.11.1291. PMID: 5116471.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5116471/

113. Mann GV, Spoerry A, Gray M, Jarashow D. Atherosclerosis in the Masai. Am J Epidemiol. 1972 Jan;95(1):26-37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121365. PMID: 5007361.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5007361/

114. Baxter NT, Schmidt AW, Venkataraman A, Kim KS, Waldron C, Schmidt TM. Dynamics of Human Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Response to Dietary Interventions with Three Fermentable Fibers. mBio. 2019 Jan 29;10(1):e02566-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02566-18. PMID: 30696735; PMCID: PMC6355990.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30696735/

115. Xiong RG, Zhou DD, Wu SX, Huang SY, Saimaiti A, Yang ZJ, Shang A, Zhao CN, Gan RY, Li HB. Health Benefits and Side Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Foods. 2022 Sep 15;11(18):2863. doi: 10.3390/foods11182863. PMID: 36140990; PMCID: PMC9498509.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9498509/

116. De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, Collini S, Pieraccini G, Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Aug 17;107(33):14691-6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. Epub 2010 Aug 2. PMID: 20679230; PMCID: PMC2930426.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20679230/

117. Campbell A, Gdanetz K, Schmidt AW, Schmidt TM. H2 generated by fermentation in the human gut microbiome influences metabolism and competitive fitness of gut butyrate producers. Microbiome. 2023 Jun 15;11(1):133. doi: 10.1186/s40168-023-01565-3. PMID: 37322527; PMCID: PMC10268494.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37322527/

118. Mutuyemungu E, Motta-Romero HA, Yang Q, Liu S, Liu S, Singh M, Rose DJ. Megasphaera elsdenii, a commensal member of the gut microbiota, is associated with elevated gas production during in vitro fermentation. Gut Microbiome (Camb). 2023 Dec 21;5:e1. doi: 10.1017/gmb.2023.18. PMID: 39290659; PMCID: PMC11406407.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39290659/

119. Modesto A, Cameron NR, Varghese C, Peters N, Stokes B, Phillips A, Bissett I, O'Grady G. Meta-Analysis of the Composition of Human Intestinal Gases. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Aug;67(8):3842-3859. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07254-1. Epub 2021 Oct 8. PMID: 34623578.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34623578/

120. Dixon BJ, Tang J, Zhang JH. The evolution of molecular hydrogen: a noteworthy potential therapy with clinical significance. Med Gas Res. 2013 May 16;3(1):10. doi: 10.1186/2045-9912-3-10. PMID: 23680032; PMCID: PMC3660246.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23680032/

121. Ohta S. Molecular hydrogen as a novel antioxidant: overview of the advantages of hydrogen for medical applications. Methods Enzymol. 2015;555:289-317. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.038. Epub 2015 Jan 21. PMID: 25747486.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25747486/

121a. Cosun Nutrition Center. Factsheet Consumption of protein in the Netherlands. Intake of plant and animal protein based on the sixth Dutch National Food Consumption Survey 2019-2021, accessed 29 October 2024

https://cosunnutritioncenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Factsheet-C…

121b. Cosun Nutrition Center. Factsheet Plant based proteins. Accessed 29 October 2024.

https://cosunnutritioncenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Fact-sheet-…

122. Lépine G, Fouillet H, Rémond D, Huneau JF, Mariotti F, Polakof S. A Scoping Review: Metabolomics Signatures Associated with Animal and Plant Protein Intake and Their Potential Relation with Cardiometabolic Risk. Adv Nutr. 2021 Dec 1;12(6):2112-2131. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab073. PMID: 34229350; PMCID: PMC8634484.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34229350/

123. Pinckaers, P. J., Domić, J., Petrick, H. L., Holwerda, A. M., Trommelen, J., Hendriks, F. K., ... & van Loon, L. J. (2024). Higher muscle protein synthesis rates following ingestion of an omnivorous meal compared with an isocaloric and isonitrogenous vegan meal in healthy, older adults. The Journal of nutrition, 154(7), 2120-2132.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022316623727235

Ergothioneine

123a. Jew, Stephanie, et al. "Nutrient essentiality revisited." Journal of Functional foods 14 (2015): 203-209.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1756464615000286

124. Tian X, Thorne JL, Moore JB. Ergothioneine: an underrecognised dietary micronutrient required for healthy ageing? Br J Nutr. 2023 Jan 14;129(1):104-114. doi: 10.1017/S0007114522003592. PMID: 38018890; PMCID: PMC9816654.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38018890/

125. Fong ZW, Tang RMY, Cheah IK, Leow DMK, Chen L, Halliwell B. Ergothioneine and mitochondria: An important protective mechanism? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024 Sep 24;726:150269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.150269. Epub 2024 Jun 19. PMID: 38909533.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38909533/

126. Power, R. C., Salazar-García, D. C., Straus, L. G., Morales, M. R. G., & Henry, A. G. (2015). Microremains from El Mirón Cave human dental calculus suggest a mixed plant–animal subsistence economy during the Magdalenian in Northern Iberia. Journal of archaeological science, 60, 39-46.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305440315001296

127. O'Regan, H. J., Lamb, A. L., & Wilkinson, D. M. (2016). The missing mushrooms: Searching for fungi in ancient human dietary analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science, 75, 139-143.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305440316301455

128. Oldest evidence for the use of mushrooms as a food source.Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. April 16, 2015

https://www.mpg.de/9173780/mushrooms-food-source-stone-age

129. Wakchaure, G. C. (2011). Production and marketing of mushrooms: global and national scenario. Mushrooms-cultivation, marketing and consumption, 15-22.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235951347_Production_and_Marke…

130. Gründemann D, Hartmann L, Flögel S. The ergothioneine transporter (ETT): substrates and locations, an inventory. FEBS Lett. 2022 May;596(10):1252-1269. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14269. Epub 2022 Jan 7. PMID: 34958679.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34958679/

131. Halliwell B, Cheah I. Are age-related neurodegenerative diseases caused by a lack of the diet-derived compound ergothioneine? Free Radic Biol Med. 2024 May 1;217:60-67. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.03.009. Epub 2024 Mar 14. PMID: 38492784.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38492784/

132. Jenny KA, Mose G, Haupt DJ, Hondal RJ. Oxidized Forms of Ergothioneine Are Substrates for Mammalian Thioredoxin Reductase. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Jan 19;11(2):185. doi: 10.3390/antiox11020185. PMID: 35204068; PMCID: PMC8868364.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35204068/

Phytochemicals

133. Wink, M. (2011). Annual plant reviews, biochemistry of plant secondary metabolism. John Wiley & Sons.

https://books.google.nl/books?hl=nl&lr=&id=K8P5gScLklYC&oi=fnd&pg=PP7&d…

134. Wink M. Evolution of secondary metabolites from an ecological and molecular phylogenetic perspective. Phytochemistry. 2003 Sep;64(1):3-19. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00300-5. PMID: 12946402.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12946402/

135. Pan MH, Lai CS, Dushenkov S, Ho CT. Modulation of inflammatory genes by natural dietary bioactive compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2009 Jun 10;57(11):4467-77. doi: 10.1021/jf900612n. PMID: 19489612.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19489612/

136. Seymour EM, Bennink MR, Bolling SF. Diet-relevant phytochemical intake affects the cardiac AhR and nrf2 transcriptome and reduces heart failure in hypertensive rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2013 Sep;24(9):1580-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.01.008. Epub 2013 Mar 22. PMID: 23528973; PMCID: PMC3893821.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23528973/